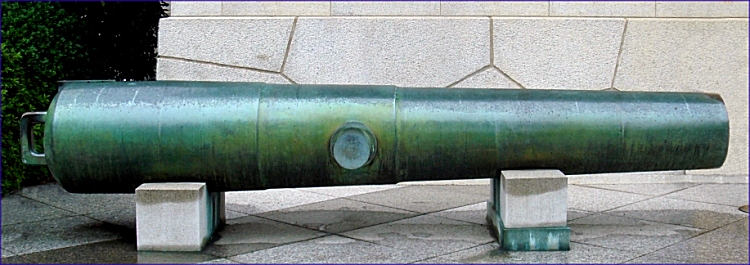

A massive but elegant and beautifully made cannon, cast in bronze in 1849 at Satsuma, originally mounted at Kagoshima, Japan.

It’s often said that Edwards Deming was “the American who taught the Japanese about quality.” In fact, there was even a book about Deming that made that claim in the title.

But is it true? For several reasons, I would say, No, it’s not true.

First of all, Deming didn’t just teach Japanese people. He would teach anybody who would listen. Many Japanese scientists, engineers, and business leaders listened and learned. Few in the U.S.A. did. The consequences are well enough known.

Secondly, Deming actually didn’t teach about quality. As a statistician, Deming taught how to quantify quality. The general Japanese cultural preference for doing things well pre-existed Deming’s teachings but, prior to introduction of his methods, that quality was difficult to measure or express.

There are numerous examples of a Japanese preference for doing things well: the elegant simplicity of tradition Japanese architecture, the beauty and technical sophistication of the katana (the sword of the samurai), and the huge 11.4″ bore bronze cannon pictured at the beginning of this article, beautifully made but, unknown to the Japanese, completely obsolete when it was cast. They only discovered this four years later when Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Edo bay (modern Tokyo bay) in 1853 in large ships with cannon able to fire exploding shells, thus ending Japan’s long self-imposed international isolation.

A couple of videos about woodworking in Japan illustrate the point about a pre-existing Japanese preference for doing things well.

This first video is of a planing competition, of all things, in which people use hand-made wooden planes to cut extremely thin strips of wood from a timber, the thinnest of which could hide behind a single human blood cell. And these planes are adjusted with hammer taps. There are no screw adjustments, probably because a screw adjustment would be too coarse. The fineness and sharpness of these plane blades is hard to comprehend.

This second video is about traditional sashimono woodworking, primarily used in furniture making. Forests are one of the few things abundant in Japan, so woodworking has been able to develop to a very high state there.

The craft approach to quality was fine in an isolated and pre-industrial Japan before Perry’s arrival, but with the Meiji restoration 15 years later, the industrial revolution began to take hold in Japan and such craft approaches met their limits.

In an effort to modernize during the Meiji era, the people around the emperor chose to follow the model of the German empire, which had asserted itself around the same time in Europe. This was a disastrous decision, but ended up having important implications in the acceptance of Deming’s ideas.

Unfortunately, many of the features of the German government, military, and universities were adopted in Japan. This led to many of the same problems seen in other countries influenced by the situational ethics, elitism, and supremacist ideas of late 19th-century progressives in Germany.

In Germany itself these ideas provided fertile ground for the militarism and aggression of the kaiser and his general staff, leading to the First World War and shocking German brutality against civilians in conquered lands. When the National Socialists started the Second World War they repeated the practices of the first war, but the scale of their brutality against civilians, of which only half constituted the Jewish holocaust, dwarfed by several orders of magnitude the German outrages of the Great War.

The Teutonic top-down command and control system and supremacist ideas had similar effects when imported to Japan, leading to political repression at home and to the slaughter of millions of Chinese and other civilians during attempts to establish the so-called Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Even the U.S.A. wasn’t immune to this German/progressive/socialist poison. Under the leadership of the vicious racist and progressive Woodrow Wilson (racism was considered progressive at the time), the Democratic party reconstituted its terrorist arm, the Ku Klux Klan, went back to murdering blacks (with a few Jews, Catholics, immigrants, and Republicans thrown in for good measure), doubled down on their Jim Crow laws, and adopted such progressive ideas as eugenics and euthanasia. They instituted the New Deal (a newer version of what had been known as “war socialism” during the Great War) in the fantastic belief that massive government intervention in the economy could somehow somehow correct the fatally flawed monetary policies of the French and American governments that caused the Great Depression.

And these progressive/socialist mistakes fed off of each other. When the National Socialists came to power in Germany they actually borrowed American eugenics laws as a model for their Jew-hating racial purity laws.

The point from the perspective of Deming’s work is that, in every case, these German-derived socialist/progressive ideas led to repression of free markets. Instead of trading with their neighbors to generate prosperity, the worst of these socialist/progressive (that is, fascist) nations — Germany, Japan, and Italy — simply invaded their neighbors. So when the Second World War ended and Japan lay in ruins and fascism was largely discredited, Japan needed another way forward.

That’s when a tall, gangly American came to tell Japanese scientists and engineers that the way forward lay not in a massive, all powerful government, not in elitism, militarism, and conquest, but in humility, statistics, and customer service.

“You know how to build good stuff,” he might have said. “Find out what the customer wants and needs. Build it for them. Use statistics to make sure you are building it well and consistently. Get it to the customer. Then talk with the customer again to see how you did. Do it all again, getting better every time. Do that and you will conquer the world.”

And Deming was right. He really didn’t teach the Japanese about quality. More than anything, he taught, and had the statistics to prove, that we all gain through free markets, through service to our fellow men.

It’s a lesson we may need to relearn: The golden rule is better for individuals, better for society, better for neighboring peoples, a lot more fun, and a lot more profitable, than barbarism. The statistics prove it.

Copyright 2016 by Paul G. Spring. All rights reserved.