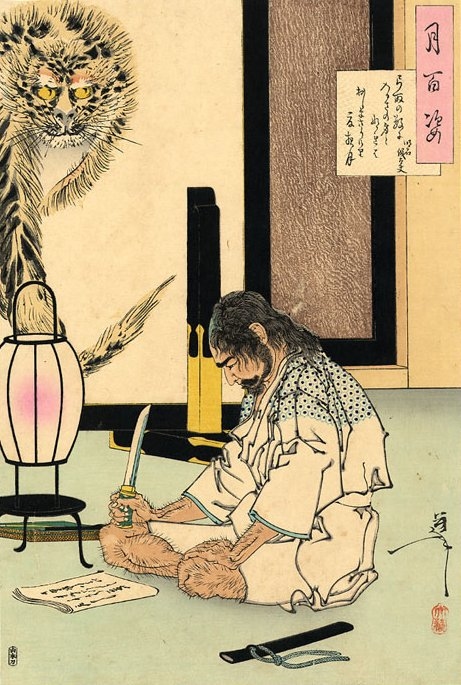

General Akashi Gidayu preparing to commit Seppuki after loosing a battle for his master in 1582. He just wrote his death poem, which is also visible in the upper right corner. Artist: Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, created about 1890.

Awhile back I wrote a post about Jim Womack’s forward to John Shook’s book Managing to Learn. One of Womack’s points was that the difference between a mass production organization and a Lean organization is that one is based on authority and the other is based on responsibility.

This difference cuts to the heart of the cultural differences between Japan and the USA. I have often had American managers tell me that the reason Lean works in Japan is that Japanese society is very hierarchical, so employees do what they are told. Without that hierarchy, they say, Lean can’t work in the USA.

Sadly, they completely misunderstand Lean and the culture of its birthplace.

In fact, Japanese society has historically been very hierarchical, but it’s a different type of hierarchy than we think of in the USA. It’s a hierarchy in which responsibility and potential consequences grow as one rises. It is American culture in which hierarchy is important and destructive.

In the USA, moving up in the hierarchy means gaining greater prestige and power — often arbitrary power. It means getting farther away from being the person who will be blamed when a scapegoat is required. It also means getting away with things generally.

Moving up in the American hierarchy seems to grant greater immunity for misdeeds. In one stunning example, one of our presidential candidates apparently embezzled 50,000 documents from her employer — the so-called email scandal. Among those 50,000 documents were about 1,000 documents related to national defense.

Embezzlement and mishandling national defense information are both felonies, each count punishable by up to ten years in prison. If the embezzler were convicted on all of these criminal violations and received the maximum sentence, she would spend over a half-million years in prison. But at this point, few serious people doubt she will be the next president of the USA.

Power. Prestige. And absolute immunity to responsibility or consequences.

While this is an extreme example, many people can tell stories of misbehavior in the workplace in which low-level employees paid the price for the misdeeds or incompetence of higher-ups.

In Japan, moving up in the hierarchy does involve the acquisition of greater power and prestige, but it’s also understood that with power and prestige comes responsibility — sometimes serious responsibility along with serious consequences for failure to meet those responsibilities.

For extreme examples, during the Second World War, many Japanese commanders committing suppuku, a complex ritual belly-cutting form of suicide — often called “harakiri” — for failing to successfully defend some remote, occupied island with few resources and no reinforcement. Never mind that the commander had done all that could be done, and had killed thousands of United State Marines. The Marines took the island, and the commander took ultimate responsibility.

The victorious allies enforced radical changes on Japanese society and culture after the war, but a strong sense of personal responsibility continues in Japanese society. A few years ago, when that fake scandal of Toyotas supposedly driving away of their own volition caught the fancy of the media, Toyota’s CEO publicly wept as he apologized for the harm to Toyota’s customers. Responsibility is taken seriously in Japan in a way almost unknown in the USA

I doubt any American has had a manager kill him- or herself for being an incompetent, a bully, or a buffoon, although I have known of examples where the sacrifice did seem more than appropriate.

At a purely practical level, I have had exceptional managers of fast-food restaurants — people who deal with many young and inexperienced employees — tell me that one of the biggest challenges in training first-time supervisors is getting them to understand that the position is not about being able to wield power over their peers, but that it is a position of responsibility. One told me that his primary reason for cutting an employee out of a supervisor track, once started, is that the employee can’t grasp this principle; It’s not about the power and prestige. It’s about responsibility and striking a balance between the needs of the company, the customer, and the employee.

Unfortunately, I’ve seen many other (inadequate) managers who don’t understand this concept at all. Obviously they can’t convey this important management principle to young people (and not-so-young people) as they move through life and up the pecking order in organizations. The result is that the dysfunctional top-down, command-and-control approach to management is perpetuated.

This widespread failure to understand that supervisory and management positions involve, above all else, the assumption of responsibility makes it more difficult to find and hire good managers, and to run the company well.

I can tell you from first hand experience that a Lean organization simply can’t survive the top-down, command-and-control, authority driven style of management. I dread to think of the tone that will be set, and how much worse the problem will become, when the embezzler-in-chief becomes the commander-in-chief.