Watching people trying to wrap their heads around the idea of Lean as more than a set of tools copied piecemeal from Toyota, I have noticed a two-stage problem.

First, people don’t understand what a system is, so they can’t, as Edwards Deming implored, “Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service…”

Second, they don’t understand how a Lean system differs from a mass production system.

These aren’t really all that difficult to understand, and they are really important, so let’s take a look at them.

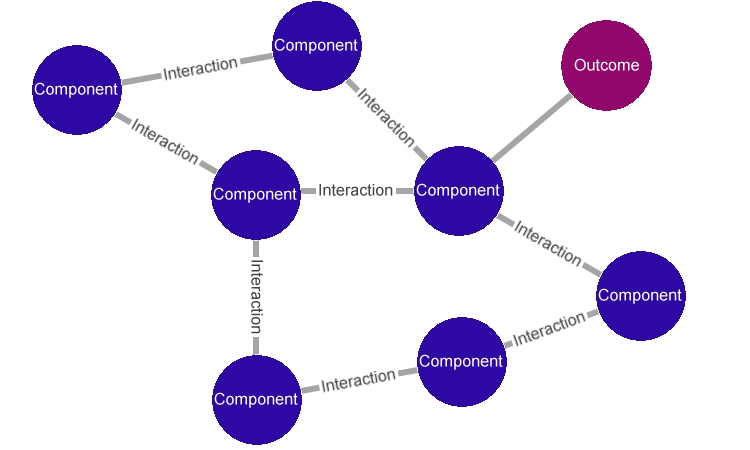

First, what is a system? As I have written before, a system is a set of components that interact to produce a particular outcome. We can diagram this pretty easily:

To create a system, an entrepreneur has only to collect all the components — the tools and people necessary to run the business, business space, suppliers, financing, IT resources, shippers, and related requirements — then arrange these components and the interactions between them. Such a first try at an arrangement of component and interaction probably won’t provide the exact outcome the entrepreneur had in mind, but generally the entrepreneur will understand the system well enough to adjust it and make it work.

Unless the entrepreneur has past Lean experience, the origins of the Lean organization and the mass production organization may look very similar. It’s often what happens once the business is up and running that differentiates between a mass producer and a Lean organization.

The mass producer quickly forces the system (which he can’t recognize as such) to become very rigid. Components are not allowed to change, and the interactions between components are not allowed to change.

Often, but not always, this rigidity sets in when the company grows enough to bring in managers from outside. For whatever reason these managers are either incapable of or unwilling to think in terms of a system. To these managers, production problems are not the result of a flawed component or set of components, or of flawed interactions. Instead, they are the result of flawed people. Instead of trying to find a flaw within the system, they find somebody to blame, creating huge morale and productivity problems.

The early days of Henry Ford’s production system for the Model T illustrates this well. Early on, Ford and his production managers kept fiddling with the system, fiddling with each production component until it was supplying what was needed, when it was needed, at the quality level that was needed, until they had dialed the system in well enough that they could make the moving production line work (The Machine That Changed The World documents well how they were able to do this.) For this reason the Model T production system is widely recognized as the first attempt at Lean manufacturing.

If you read between the lines from other sources, it appears that, once Ford had the moving production line working, Ford and his managers didn’t fully appreciate what they had accomplished. As the company grew, they couldn’t bring in managers to keep their Lean system working. The rigidity of the mass production system set in, and Ford was in for all kinds of trouble over the long run.

The shift from Ford’s production system being the prototype of all Lean ones to being an archetype of a mass production one hints at the difference between Lean and mass production systems. So what is the essence of the difference? Well, a Lean manager can look at our system diagram and see something profoundly important: Every component in that system is both a supplier and a customer — a suppler to at least one other component of the system, and a customer of at least one other component of the system. In short, a system is a set of components, along with the suppliers and customers to each component, and the interactions between them.

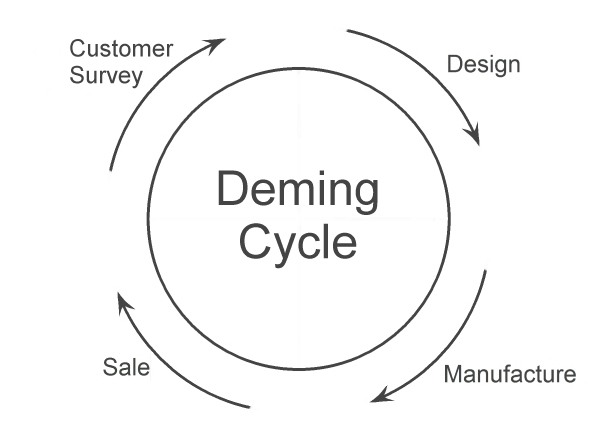

If you can recognize this, and you are managing a component in a Lean system, you recognize the component you manage as a supplier within that system, you know you have customers in that system, and you know what to do with those customers because, in his famous 1950 speech in Hakone, Japan, Edwards Deming defined how the interaction with the customer should work.

Deming laid out a cycle of 1) surveying the needs of the customer, 2) designing a way to meet those needs, 3) actually producing the goods or services necessary, and 4) selling or otherwise supplying the product to the customer. Then the cycle begins anew, with another survey of the customer, saying, in essence, “We thought we understood your needs. How did we do? How have your needs changed? How can we do better?”

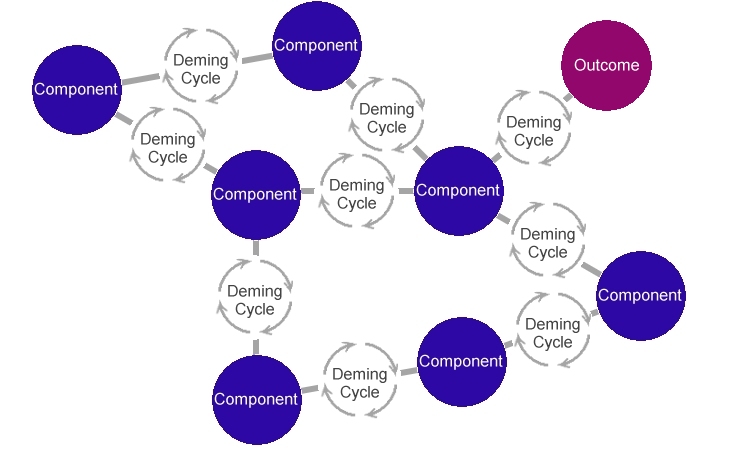

This gets to the core difference between a mass production system and a Lean system. In a mass production system the interactions between components are left undefined. In a Lean system, the interactions between components are defined by the Deming cycle. So a more precise representation of a Lean system, in which the interactions are explicitly founded on the Deming cycle, looks like this:

Founding each interaction in a Lean system on the Deming cycle allows you, or actually forces you, to “Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service…”

Most people struggle to understand what a system is. Too often the concept becomes overly complicated. It’s just a set of components that interact to produce a particular outcome. If the outcome isn’t what you expected, the system isn’t what you thought it was. To change the outcome, you must either change a component or change an interaction. To build a Lean system, the first place to change the interactions is to make sure interactions between components are based on the Deming cycle of survey, design, build, deliver, survey again, design anew, and so on. Only when you understand the needs of the customer, based on the Deming cycle, will Toyota’s tools really come into their own.

Of course there is much more to a Lean transformation than just understanding what a system is and how a Lean system differs from a mass production system. When it comes to a Lean transformation, it isn’t everything. But it’s a lot.

Copyright 2015 by Paul G. Spring. All rights reserved.