How many of us really know what we are looking for when we hire a manager? How many of can boil the crucial points of the interview down to a few questions: What problems do you see in the organization? If you get the job, what are you going to do? How are you going to do it? What evidence is there that you can do it? I suppose very few of us can, or do, take such a direct approach when considering whom to hire. Continue reading

Thoughts On Hierarchy, Authority, and Responsibility

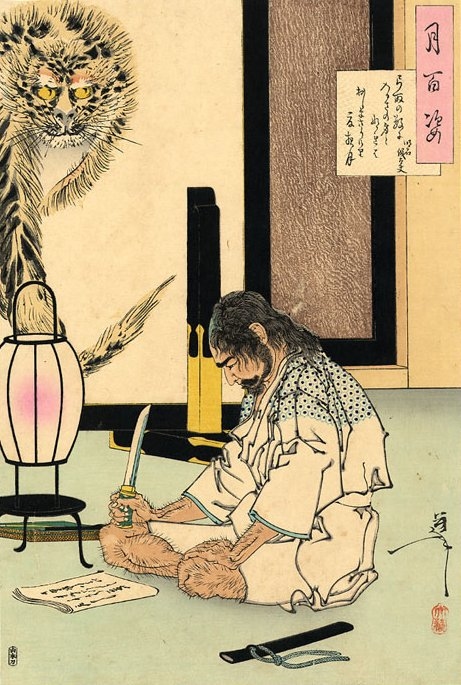

General Akashi Gidayu preparing to commit Seppuki after loosing a battle for his master in 1582. He just wrote his death poem, which is also visible in the upper right corner. Artist: Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, created about 1890.

Awhile back I wrote a post about Jim Womack’s forward to John Shook’s book Managing to Learn. One of Womack’s points was that the difference between a mass production organization and a Lean organization is that one is based on authority and the other is based on responsibility.

This difference cuts to the heart of the cultural differences between Japan and the USA. I have often had American managers tell me that the reason Lean works in Japan is that Japanese society is very hierarchical, so employees do what they are told. Without that hierarchy, they say, Lean can’t work in the USA.

Sadly, they completely misunderstand Lean and the culture of its birthplace.

In fact, Japanese society has historically been very hierarchical, but it’s a different type of hierarchy than we think of in the USA. It’s a hierarchy in which responsibility and potential consequences grow as one rises. It is American culture in which hierarchy is important and destructive.

Are Your Charts Telling You The Truth?

Lean organizations make far more use, and far more public use, of statistics and charts than do other organizations.

That’s good.

Quite often, however, in fledgling Lean organizations the information is presented in a way that tells a misleading story, or tells no useful story at all. These “statistics” sometimes seem like cartoon versions of what mass production managers believe Lean statistics should look like.

That’s bad.

In the worst cases such information in the hands of bad managers can lead to decisions that make no sense and are extremely costly to the business. Let’s take a look at some statistics and charts to see how the same data, presented differently — different chart type, different time line, and analyzed differently — can tell a very different story from the one a mass production chart can show. Continue reading

Some Quick Thoughts on “Managing To Learn”

Recently I re-read John Shook’s book on the A3 management process, Managing to Learn. Jim Womack’s forward to the book is so on point I think it bears quoting:

What is at the heart of Lean management and Lean leadership?

In addressing this question, Managing to Learn helps fill in the gap between our understanding of Lean tools, such as Value Stream Mapping, and the sustainable application of these tools. In the process it reveals:

- The distinction between old-fashioned, top down, command-and-control management and Lean management. Continue reading

What Sailboat Racing Taught Me About Toyota’s Success.

People often ask how I learned what I know about Lean. They are usually confused and disappointed when I tell them I learned a great deal of it from racing sailboats.

To the uninitiated, sailing is often seen as either idyllically romantic or as conferring great prestige on a person. These non-sailors don’t see the extreme physical and psychological demands, the analytical thinking, or the ability to gather, integrate, and act on information about a host of complex systems, that are a part of performing well at the highest level of competition — the Olympics, the America’s Cup, and the world championships for a handful of the most demanding classes.

Lean is less physically and psychologically demanding than racing small boats, but it requires many of the same skills to do it well — the persistence, the ability to find and fix small problems that others ignore, the ability to integrate many complex components into a whole with as little wasted effort, material, and time as possible, the ability to react quickly to a changing environment, having an overriding purpose (in sailing it is to win regattas; in Lean it is to please customers) and, above all, to improve, improve, improve — and improve again — every essential process and to eliminate those activities and ways of thinking that don’t add value. Continue reading

A Defense Of Deming’s Ideas In Lean

I get a fair amount of criticism about my understanding of Lean — criticism of my emphasis on the responsibilities of management, criticism of the emphasis I place on understanding and meeting the needs of the customer, criticism of trying hard to understand the teachings of Edwards Deming. And, with regard to this blog, I often get criticism for giving short shrift to the Lean tools (VSM, kanbans, andons, PDSA, and the like). Forget all that other stuff, I’m told. Concentrate on the tools.

Well, criticize away. It’s pretty much all true.

In my own defense I will say a few things.

Firstly, I probably could write more about the Lean tools, but there are many good sources of information about them and I don’t really have the time to waste repeating what somebody else has already written or said. Besides, if you’re good, you will invent some of your own tools anyway.

Secondly, I’m right.

I offer as evidence this blog post from the W. Edwards Deming Institute that examines the similarities and differences between the teachings of Edwards Deming on the one hand and, on the other hand, Lean as done by real experts like the people at the Lean Enterprise Institute, the Kaizen Institute, Mark Graban, Jim Womack, Mike Rother, and the like.

As noted by John Hunter, the author of the Deming Institute piece, “Deming didn’t advocate using a couple tools and ignoring the management system; neither does Lean manufacturing.” Furthermore, he writes that “The Lean folks people should listen to all know that deploying a few tools is not what Lean is about.”

He also notes the importance of treating employees with respect, making them an integral part of the constantly improving system. Employees are, after all, the source of all improvement.

Give this blog a read. It’s well worth a few minutes of your time.

Copyright 2016 by Paul G. Spring. All rights reserved.

Did Edwards Deming Actually “Teach The Japanese About Quality”?

A massive but elegant and beautifully made cannon, cast in bronze in 1849 at Satsuma, originally mounted at Kagoshima, Japan.

It’s often said that Edwards Deming was “the American who taught the Japanese about quality.” In fact, there was even a book about Deming that made that claim in the title.

But is it true? For several reasons, I would say, No, it’s not true.

First of all, Deming didn’t just teach Japanese people. He would teach anybody who would listen. Many Japanese scientists, engineers, and business leaders listened and learned. Few in the U.S.A. did. The consequences are well enough known.

Secondly, Deming actually didn’t teach about quality. As a statistician, Deming taught how to quantify quality. Continue reading

Just-In-Time Inventory: Everything You Need To Know, In Less Than 20 Seconds

Everything you need to know about Just-In-Time inventory can be summarize in a single word: Nothing.

Or perhaps two words: Absolutely Nothing.

Why? Because, although the term “Just-In-Time inventory” has been commonly used for many years, there is no such thing as “Just-In-Time inventory”. Continue reading

How Many Socialists Does It Take To Start A SAAB? The Logic Of Problem Solving And Decision Making.

On a recent trip to the grocery store I shambled by an otherwise nice SAAB with a “Bernie Sanders 2016” sticker on the back bumper, the hood up, and three scrawny hipster guys (late 20s going on 11) slouching around it, occassionally cranking the engine.

“Can you, like, give us a jump?” one man-child asked abruptly as I passed. (What ever happened to the simple courtesy of excusing yourself before you interrupt another person? “Excuse me, can you, like, give us a jump?”)

“Probably not. I walked. Besides, you don’t need a jump. Your engine is cranking fine. There’s nothing wrong with your battery.”

“But we need a jump.”

I was momentarily surprised that not one of these young males had any idea of how to solve the problem of a car that won’t start. That surprise quickly passed as I recognized this as one more manifestation of a very widespread problem: an inability to think rationally about problems. This inability to rationally analyze and solve problems, an inability to make rational decisions, shows up throughout our society — in our personal lives, in public policy debates, and, of course, at work.

Rational — one might even say scientific — analysis, problem solving, and decision making is a core activity for anybody working in a Lean environment, so it’s a set of skills that many people new to Lean will need to learn or refine.

“Never Underestimate The Power Of A Really Bad Leader To Cock Things Up.”

Despite the many ways that Lean transitions can fail in American business, they most often fail because of disordered personalities wreaking havoc in the organization and throwing Lean efforts off track. The harm that a single person with a disordered personality can do to an organization, even from a middle management or lower level, is difficult to believe if you don’t witness it yourself.

From the point of view of somebody trying to lead a Lean transition, the destructiveness of these people is difficult to detect if you aren’t yet accustomed to thinking in terms of a system, and/or if you haven’t yet learned to pay very careful attention to details. What’s more, these people with disordered personalities are often superficially very charming, and can be astonishingly good liars. You can’t run a Lean organization with creatures like this.

Here is an excellent primer on the interaction between leadership and personality.

More background on the video and the people who produced and appear in it is available here.

Copyright 2015 by Paul G. Spring. All rights reserved.