NASCAR Trucks race at Pocono. It’s difficult to explain even to many Americans, let alone Japanese and Europeans, the appeal of this quintessentially American cultural phenomenon; too much is lost in translation from one culture to another.

Occasionally people object that kaizen doesn’t mean, as I have often said it does, “virtuous change”. Technically, that’s true, but kaizen doesn’t mean “continuous improvement” either. Both are an attempt to capture the meaning of kaizen within Japanese culture.

Effectively translating words from one language to another can be a challenge, but translating ideas (like kaizen) is often even more difficult. Humor is more difficult yet. In fact, sometimes it’s very difficult even to translate from British English to American English, or from American English in one part of the U.S.A. to American English in another part.

With that in mind, here are a few examples to keep in mind the next time you have trouble understanding what a Japanese word means:

I have had occasion to travel in the American southeast, where, when you sit down in a restaurant, the waitress will invariably ask “How y’all doin?”

Here’s the thing: They will ask that even if you are alone, and obviously alone.

At first I found this question really disconcerting. It seems like the wrong question. After all, there is no “all”. It’s just me. Or maybe the waitress somehow judged that I must have multiple personalities and she was just trying, as southerners almost invariably do, to be polite. Eventually a Texan told me to just replay “Fahn,” and order some grits. “Do that,” he said, “and everything will be fahn.”

In any case, I can picture Japanese nationals wandering into a diner in Philadelphia, Mississippi and trying to understand the whole “How y’all doin?” “Fahn, thank you. I’d like some grits please” thing. Now what exactly does kaizen mean?

Despite the common language, even British cultural nuances can be lost in translation to Americans.

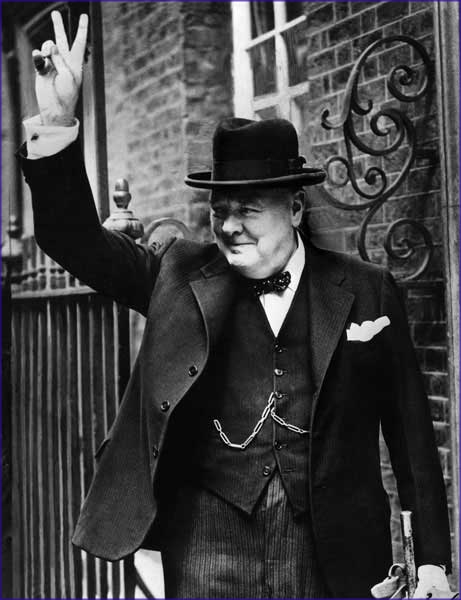

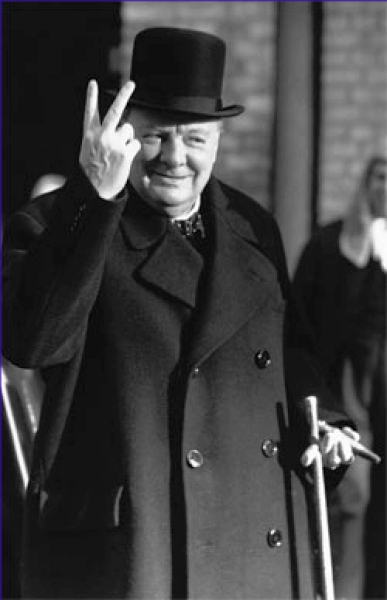

During the Second World War, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was known for flashing his trademark “V for Victory” sign. In the same period the BBC introduced many news broadcasts with the opening four notes of Beethoven’s Fifth symphony (Symphony V), notes which also happen to follow the beat of the Morse code for the letter V, dit-dit-dit-dah. So Churchill’s gesture was part of what we would today call staying on message.

However, you can find photos and videos of Churchill turning the “V for Victory” sign around, with the back of the hand out, signaling not “V for Victory” but “Up yours”. That “Up yours” sign has a well-known and significantly less socially acceptable counterpart in the American vernacular. Being more laid back than their British cousins, however, Americans use only a single finger.

The two-finger “up yours” salute was well known in Britain for centuries because of it’s association with the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, where badly outnumbered British longbowmen slaughtered vast numbers of mounted French knights and won the day. In the years after the battle, when the French caught an English bowman, they would cut off the Englishman’s index and middle fingers — fingers used to draw the bow — permanently disabling the bowman.

Knowing of this practice, when they met the French in battle, the British would defiantly shake their bow fingers at the French as a sign that they were still able and willing to thrash an enemy, even against long odds. Turn that sign around and you have “V for Victory.” So flashing the “V for Victory” or “Up yours” in the context of Britain fighting outnumbered and alone against National Socialist Germany and their collaborators in a captive Europe was culturally appropriate. Not knowing the history, the “V for Victory” has far less meaning to Americans than it did to the British. Two nations divided by a common language indeed.

The French and British eventually gave up killing each other on and around the fields of Flanders, hopped in their cars, and took their rivalry to the roads of Le Mans. The Englishman W.O. Bentley built cars to race against his arch-rival, the Italian-born naturalized Frenchman Ettore Bugatti.

Bentley and Bugatti had different approaches to racing. When Bentley wanted to go faster, he built a bigger engine. The low-stress engines and heavy cars were very reliable.

When Bugatti wanted to go faster, he built small but powerful high-revving engines and put them in lighter and more streamlined cars. They were fast, but the high-strung Bugattis were less reliable than the Bentleys.

Bentley cars won at the 24 Hours of Le Mans six times in the 1920s and 1930s. Bugattis won twice in the immediate pre-WW2 era. Unimpressed by the large and heavy Bentleys, and perhaps harboring some of the old French resentment of being beaten by the British, Bugatti sniffed that “Bentley builds the fastest lorries in Europe.”

Here we have another lost-in-translation problem.

For the uninitiated, one could simply translate “lorry” as “truck”, but that would be a pedestrian translation (if I may use that term in referring to a motor vehicle). It doesn’t really get to the core of Bugatti’s insult because a lot of Americans really like trucks.

Where some Europeans spend their weekends watching extraordinarily ungainly-looking cars race in Formula 1, some Americans prefer to spend their weekends watching trucks drive in circles on a NASCAR track. For many Americans, having the fastest truck in Europe would be really cool if Europe were cool, which it isn’t, so having the fastest truck in Europe is like having the fastest truck in New York City — There’s probably nothing wrong with it, but overall it’s probably just not very interesting. So Bugatti’s insult depends on context.

Now, on the weekends when there are no NASCAR trucks to watch, Americans think nothing of throwing a bunch of guns in the back of the truck and heading off into the neighboring state to go pig hunting.

That’s probably not something you should do in Europe. Again, there is potential for the lost-in-translation problem.

With their history, if you cross a European border with a truckload of firearms while talking about hunting for pigs to shoot, you could create an international crisis. Given their national hatreds and the way they express them, talk of hunting pigs has often meant serious trouble — the start of a genocidal war, for example — in Europe.

Of course, whether in the U.S.A., in the U.K., in France, or anyplace else in Europe, if you cross a border in a Bentley stuffed with guns, people will naturally assume you are a drug dealer, so we have a common language and a common culture in certain respects.

Still, the point is that Frenchmen, Englishmen, and Americans really aren’t going to understand each other on the concept of the fastest lorry in Europe. So let me translate.

It seems to me that the proper translation into American English of Bugatti’s insult is this: “Bentley builds the fastest U-Hauls in Europe.”

Now that’s insulting. And it’s completely undecipherable by anybody except an American.

So the next time somebody starts throwing Japanese words around and saying they mean this or that, or don’t mean this or that, try to understand the cultural context in which that word is used. And just realize that you may never get a perfect translation. But you might figure out that “virtuous change” is about as close as you are likely to get to a culturally appropriate translation of kaizen.

Copyright 2015 by Paul G. Spring. All rights reserved.