As a SCORE counselor I see a lot of business plans — some real, many samples from the internet and other sources. Almost all of them begin by asserting “We will do X, Y, and Z.” Almost none begin by asserting “The customer wants us to do A, B, and C.”

When I point this out, people instinctively understand that the one form is better than the other. The one implies a business based on the will of management. The other implies a complete strategy fashioned around the needs of the customer — a Lean strategy.

To some people, saying that Lean is a strategy fashioned around the needs of the customer, well, Them’s fightin’ words.

So let’s have the fight.

There are two questions to settle: Is this Lean? Is it a strategy?

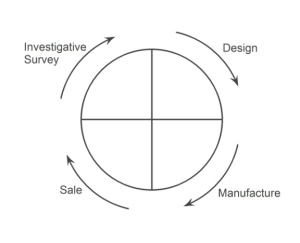

Edwards Deming, in his famous 1950 speech in Hakone, asserted that the key to a successful business strategy is a cycle of product design, manufacture, and sale that starts with a careful statistical investigative survey of customer needs.

The business plan built on the needs of the customer seems to have the customer survey part handled. But what about the design and manufacturing?

“The customer wants us to do A, B, and C,” implies that “The customer doesn’t particularly want us to do things that aren’t A, B, and C.”

This should sound familiar to the experienced Lean practitioner. We seek to eliminate those activities, things, and time that don’t add value for the customer. We are trying provide those products and services which customers — or potential customers — will value above all available alternatives. We are trying to do A, B, and C, and not do things that aren’t A, B, and C.

This is fundamental to Lean, but it often slips our minds if we get wrapped up in trying to implement kanban systems, conduct “kaizen events”, and so on.

So serving customers is a foundational element of Lean. But is serving the customer really the basis of a strategy?

In a word, Yes.

McGill University professor Henry Mintzberg has developed ideas about strategy that are immensely useful to understanding Lean. He has studied strategy, thought about it, and written about it, for decades. While it’s a complex subject, Mintzberg’s ideas have often been summarize like this:

“Strategy is a pattern in a stream of decisions.”

Without (I hope) oversimplifying Mintzberg’s work, I believe we can construct several similar descriptions that, taken together, can give greater insight into the meaning of strategy and the problem of defining it.

For example, we might say “The strategy of an organization is whatever that organization says is its strategy.” Put more directly this becomes “Strategy is the stated intention of the organization.”

Nice theory. Sometimes it’s actually true.

Consider another example, a military organization in time of war. We might rightly say that “Strategy is revealed by the pattern in a stream of orders.” Most of the time, in most military organizations, this is true.

Here let me restate here the original proposition that “Strategy is a pattern in a stream of decisions.” But decisions may or may not be translated into actions. With that in mind, most of us with real work experience can understand another variant of our basic proposition: “Strategy is a pattern in a stream of actions.”

So strategy might be defined, among other ways, as either the intent of the organization, or as the overall pattern to the stream of the orders, or of the stream of decisions, or of the stream of actions.

In practice, if intent, orders, decisions, and actions within the organization are in conflict one with another, it will be difficult to discern what strategy the organization is actually trying to pursue. Keep in mind, however, that actions always speak louder than words. In any case, an organization like this will be troubled.

On the other hand, when these elements—intent, orders, decisions, and actions—are congruent, the strategy of the organization becomes quite clear. If the actual strategy of the organization (that is, the combination of it’s stated intent, its decisions, and its actions) leads to products and services that customers desire and judge to be of greater value than any available alternative, the organization is likely to be very successful.

An examination of history also supports my contention that Lean is a strategy of serving the customer.

What we know as Lean began in Japan after the Second World War as a way of thinking about why the business exists — that is, to put desperate people to remunerative work providing goods and/or services for customers — preferably oversees customers, as Deming urged. To succeed, these businesses had to provide goods and services that customers anywhere in the world would value above all available alternatives, a very high bar indeed.

This was their intent.

The way a Lean organization is structured, staffed, and managed, and the way it learns, are all a manifestation of a stream of decisions and actions taken within the organization. The familiar tools of Lean are simply the manifestation of such decisions and actions. These are the decisions and actions of our deeper definition of strategy.

What we see, then, in a truly Lean organization is a well-defined intent in combination with specific patterns in streams of decisions and actions, all of which are congruent, and all of which are intended to do A, B, and C, and not do things that aren’t A, B, and C.

This is why I understand that Lean is a strategy of serving the customer. This is why you should understand it too.

Copyright 2014 by Paul G. Spring. All rights reserved.