I recently had to sit through a meeting at which a few people proudly tossed into the air such trendy terms as “thinking outside the box,” and “internal customer”.

They seemed oblivious to the fact that “thinking outside the box” is such a commonplace today that its invocation signals its exact opposite, that is, an utter lack of thought that fits neatly within the confines of the very small and conventional cardboard shipping box it arrived in.

But what about “internal customer”? Surely that is a good insight, is it not?

It is not.

Unless, that is, you work in a mass production environment, where talk of an “internal customer” is one more ad hoc solution added to a collection of ad hoc solutions trying unsuccessfully — impossibly, really — to solve the problems inherent in a mass production system.

In a mass production environment, talk of internal customers implies external customers. Such talk reveals the inner thinking of most people in that environment — that customers are external to what they do, a sort of other, somebody to be dealt with by salesmen or customer service representatives or somebody like that. Whoever deals with them, they aren’t our problem.

The underlying cause of this way of thinking is that in a mass production environment people are hired to perform certain specific tasks. This task orientation prohibits consideration of any factors outside of the immediate task for which a person was hired. It allows no consideration of the needs of the customer. Talk of “internal customers” won’t change this fundamental view. The only way to change it is to make consideration of the needs of the customer a part of the task.

In a Lean environment, on the other hand, the idea of an internal customer makes no sense. To understand this, I go back to basics, and there is little more basic to the conception of Lean than Edwards Deming’s 1950 speech in Hakone, Japan.

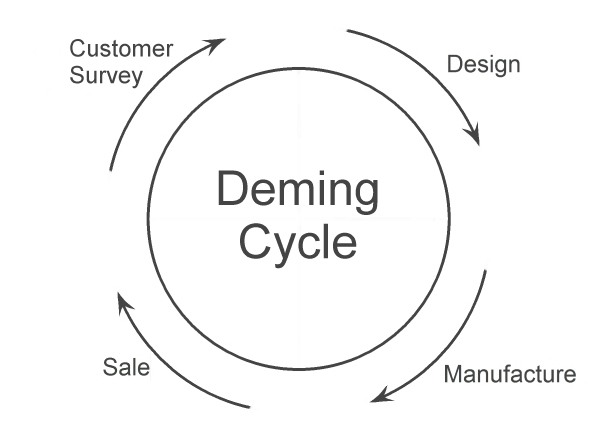

In that speech Deming laid out a cycle of business, which starts with a survey of the needs of the customer.

Given a good understanding of the needs of the customer, the product or service is designed, then produced and made available to the customer. At this point the customer is surveyed again, saying in effect, “This is what we understood you needed. How did we do? What has changed? What do we need to do different next time?”

There is another basic concept associated with Deming’s cycle: the identity of the customer. If you have read my recent posts about understanding the customer, you know that I assert that at the most basic and important level the customer is anybody who receives something of value in exchange for something of value.

Another basic idea upon which Deming placed great importance was thinking in terms of a system. A system is simply a set of components that interact to produce a particular outcome. If you want to change the outcome, you must either change a component, or change the interactions between components.

If we put all these ideas together — the cycle of business starting with and revolving around continuing surveys of the needs of the customer, the definition of the customer as one who receives value, and the system that can only be changed by changing a component or interaction — we should be able to see that the customer is inherently a component of the system. The customer is arguably the most important component of the system because businesses are started to serve the customer, and they survive by serving the customer.

The changing needs of the customer — anybody who receives something of value — leads to a constant ripple of change through the Lean system. One component changes, and components and interactions that feed into that first component adapt so the desired outcome can be produced. This is why a Lean system is constantly changing, why the need for “continuous improvement”.

And remember that anybody who is a part of the system can be a customer (in fact, if somebody in the system isn’t receiving something of value, one has to wonder why they are there). If I receive some paperwork that tells me what step to perform next, that paperwork has value to me if it’s right, and is of little or no value to me if it is wrong. I am grateful if it is right, troubled if it is wrong. Gratitude has value. Trouble, not so much.

So the idea of an internal customer doesn’t, and simply can’t, work in a Lean system. The Lean system is loaded with customers, with people who receive things of value, and they are all inherently part of the system. Without them you have a very different system — a mass production system. Customers are inherent components of the Lean system, so they are neither internal nor external. They are just customers.

Copyright 2015 by Paul G. Spring. All rights reserved.