Watching people trying to wrap their heads around the idea of Lean as more than a set of tools copied piecemeal from Toyota, I have noticed a two-stage problem.

First, people don’t understand what a system is, so they can’t, as Edwards Deming implored, “Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service…”

Second, they don’t understand how a Lean system differs from a mass production system.

These aren’t really all that difficult to understand, and they are really important, so let’s take a look at them.

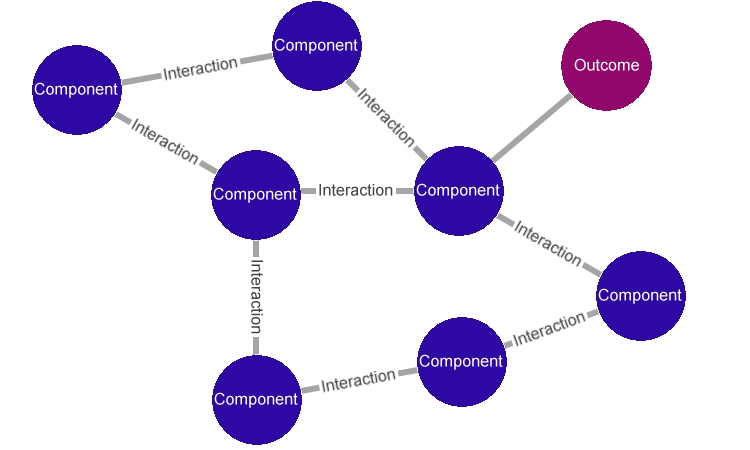

First, what is a system? As I have written before, a system is a set of components that interact to produce a particular outcome. We can diagram this pretty easily:

To create a system, an entrepreneur has only to collect all the components — the tools and people necessary to run the business, business space, suppliers, financing, IT resources, shippers, and related requirements — then arrange these components and the interactions between them.

Such a first try at an arrangement of component and interaction probably won’t provide the exact outcome the entrepreneur had in mind, but generally the entrepreneur will understand the system well enough to adjust it and make it work.

Unless the entrepreneur has past Lean experience, the origins of the Lean organization and the mass production organization may look very similar. It’s often what happens once the business is up and running that differentiates between a mass producer and a Lean organization.

Often, the mass producer quickly forces the system (which he can’t recognize as such) to become very rigid. Components are not allowed to change, and the interactions between components are not allowed to change. Management enforces this.

On the other hand, a Lean manager can look at our system diagram and see something profoundly important: Every component in that system is both a supplier and a customer — a suppler to at least one other component of the system, and a customer of at least one other component of the system. In short, a system is a set of components — with each component both a supplier and a customer to some other component — and the interactions between componenets. Interactions between customer components and supplier components are crucially important in the Lean system.

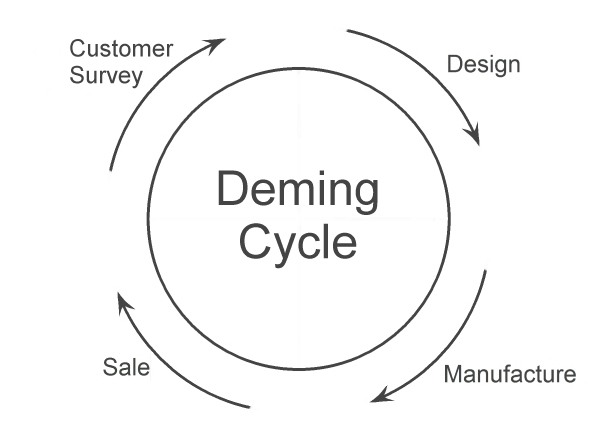

If you can recognize this, and you are managing a component in a Lean system, you recognize the component you manage as a supplier within that system, you know you have customers in that system, and you know what to do with those customers because, in his famous 1950 speech in Hakone, Japan, Edwards Deming defined how the interaction with the customer should work.

Deming laid out a cycle of 1) surveying the needs of the customer, 2) designing a way to meet those needs, 3) actually producing the goods or services necessary, and 4) selling or otherwise supplying the product to the customer. Then the cycle begins anew, with another survey of the customer, saying, in essence, “We thought we understood your needs. How did we do? How have your needs changed? How can we do better?”

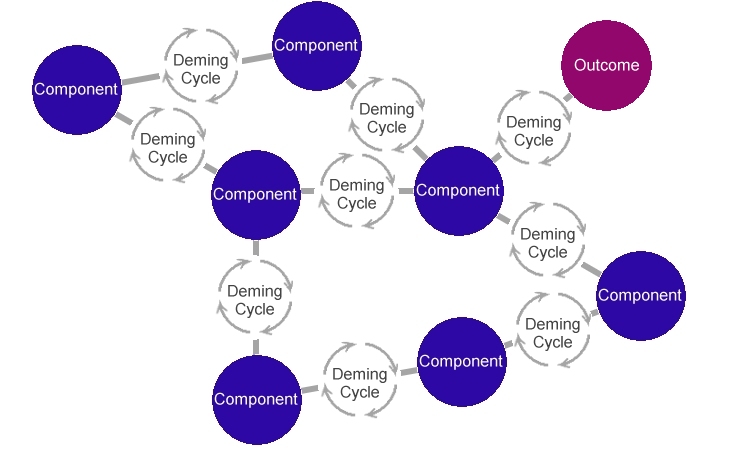

This gets to the core difference between a mass production system and a Lean system. In a mass production system the interactions between components are left undefined. They are largely left up to the will of the manager.

In a Lean system, the interactions between components are defined by the Deming cycle. So a more precise representation of a Lean system, in which the interactions are explicitly founded on the Deming cycle, looks like this:

Founding each interaction in a Lean system on the Deming cycle allows you, or actually forces you, to “Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service…”

To reiterate, a system is just a set of components that interact to produce a particular outcome. If the outcome isn’t what you expected, the system isn’t what you thought it was. To change the outcome, you must either change a component or change an interaction.

To build a Lean system, generally the place to start is to make sure interactions between components are based on the Deming cycle of survey, design, build, deliver, survey again, design anew, and so on. Only when you understand the needs of the customer, based on the Deming cycle, will Toyota’s tools really come into their own.

Of course there is much more to a Lean transformation than just understanding what a system is and how a Lean system differs from a mass production system. When it comes to a Lean transformation, it isn’t everything. But it’s a lot.